August 6 - 8, 2025

Final Refinements and Project Presentation

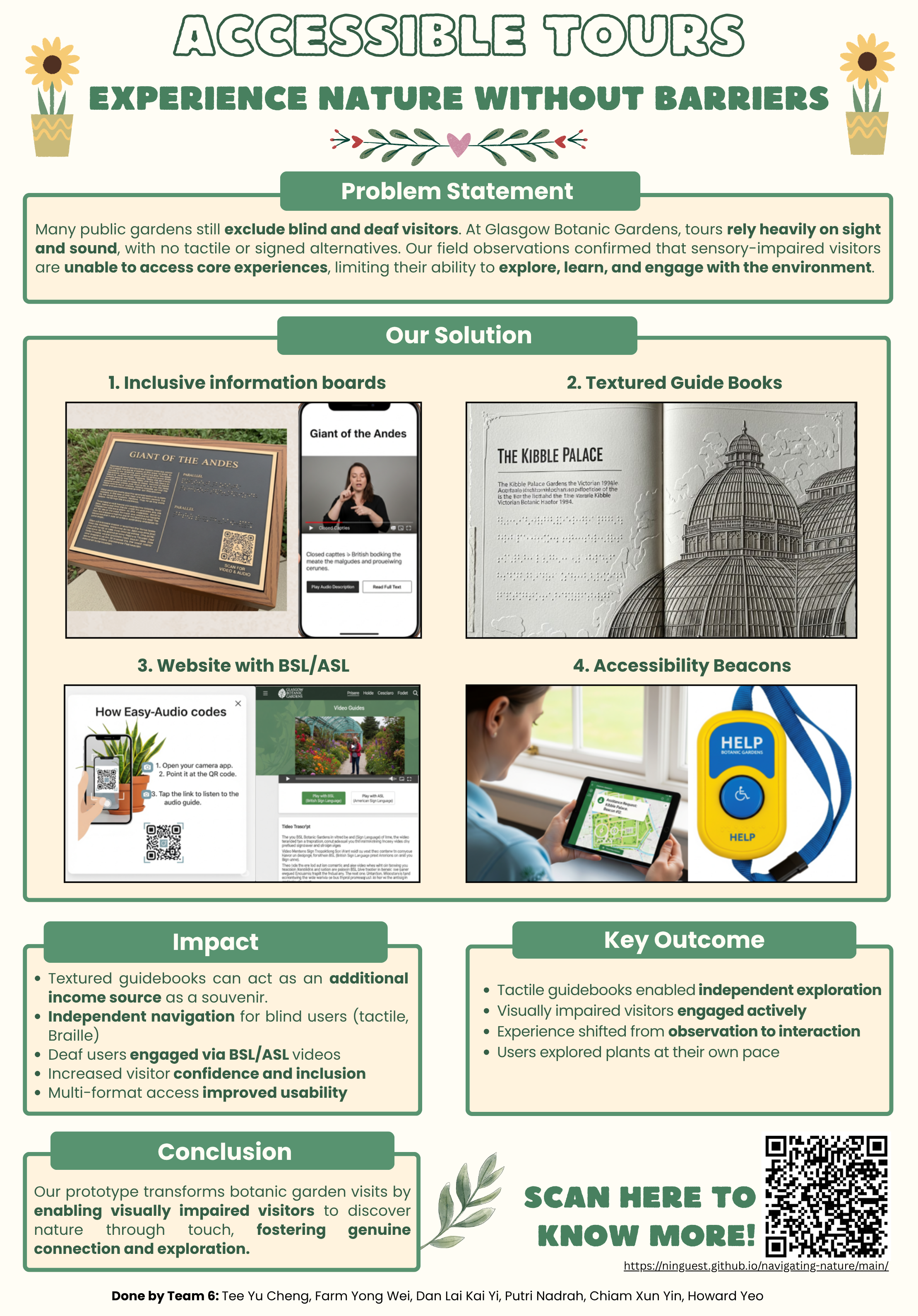

In the final project phase, we implemented feedback from our internal testing and prepared our final deliverables, including the project webpage.

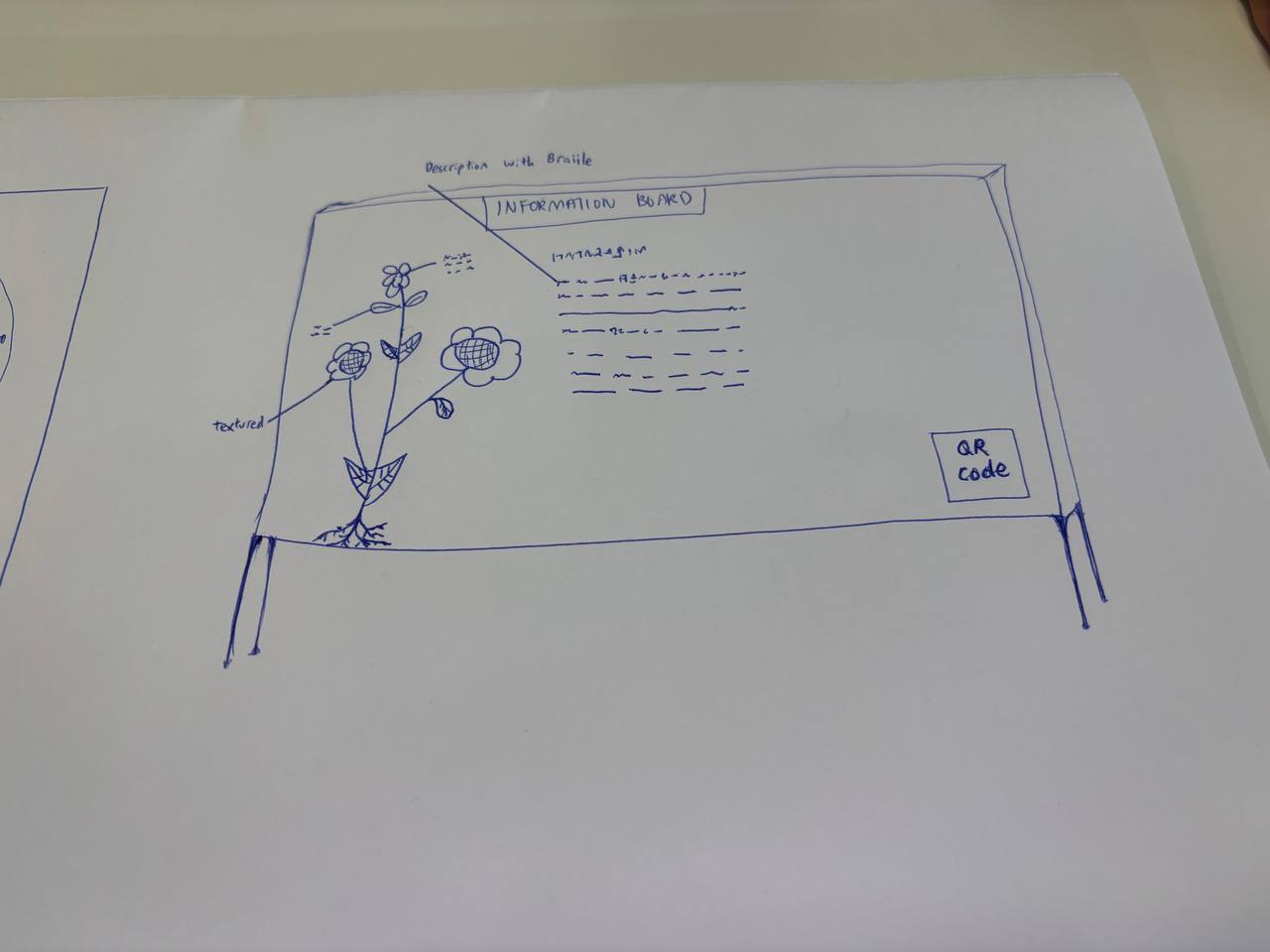

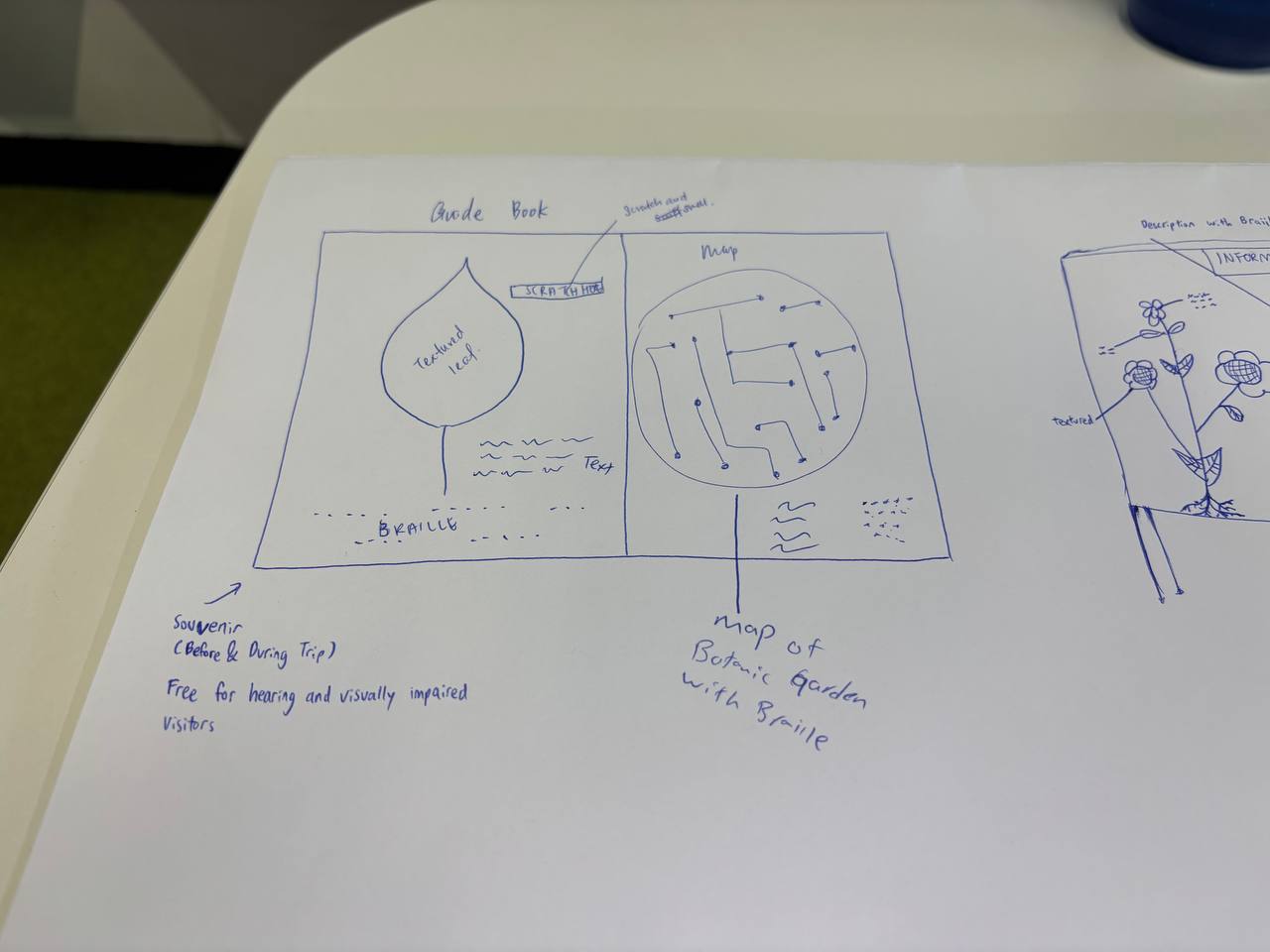

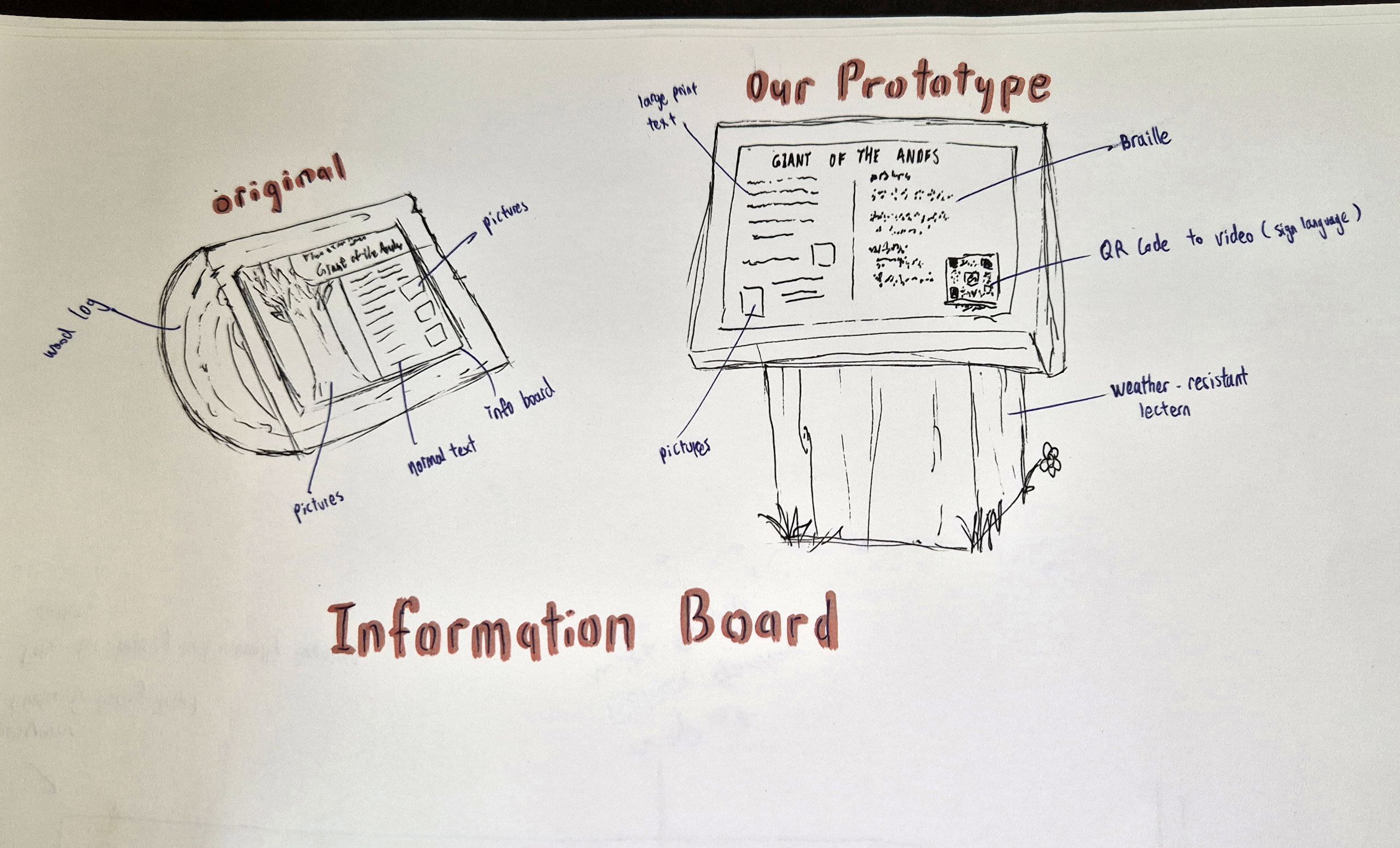

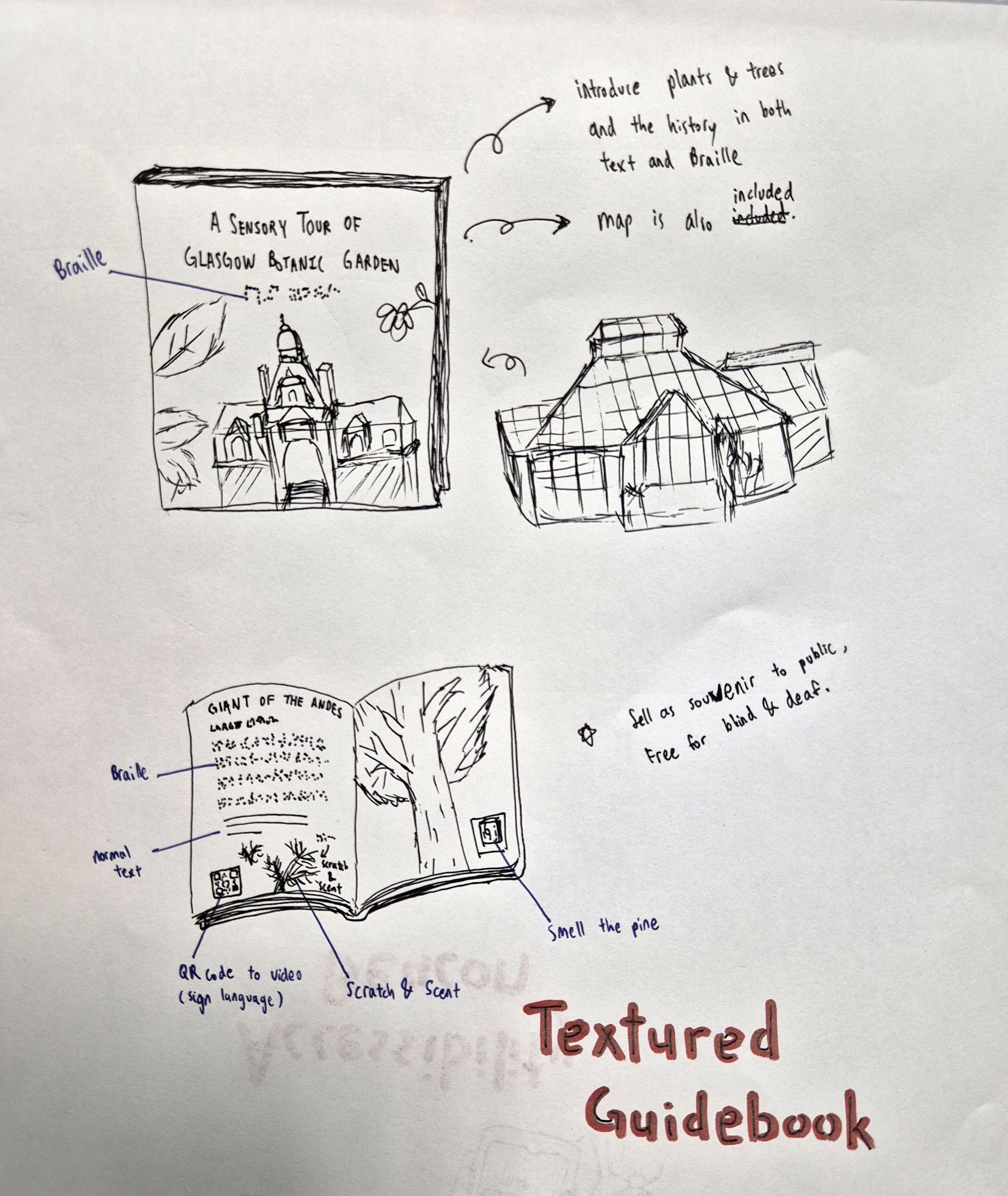

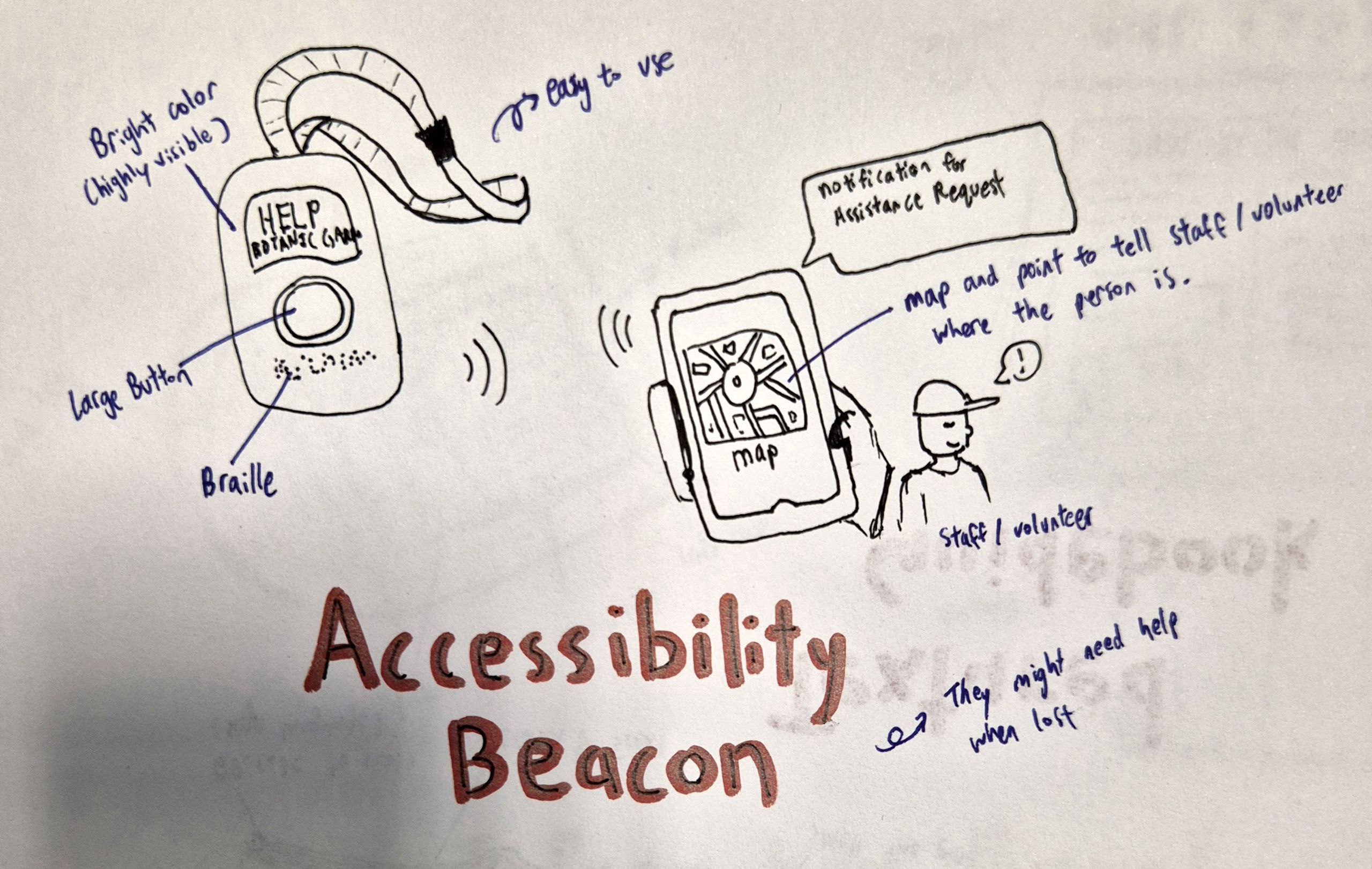

We refined tactile design specifications, repositioned braille features, improved QR code accessibility, and polished the user interface to improve clarity and ease of use.

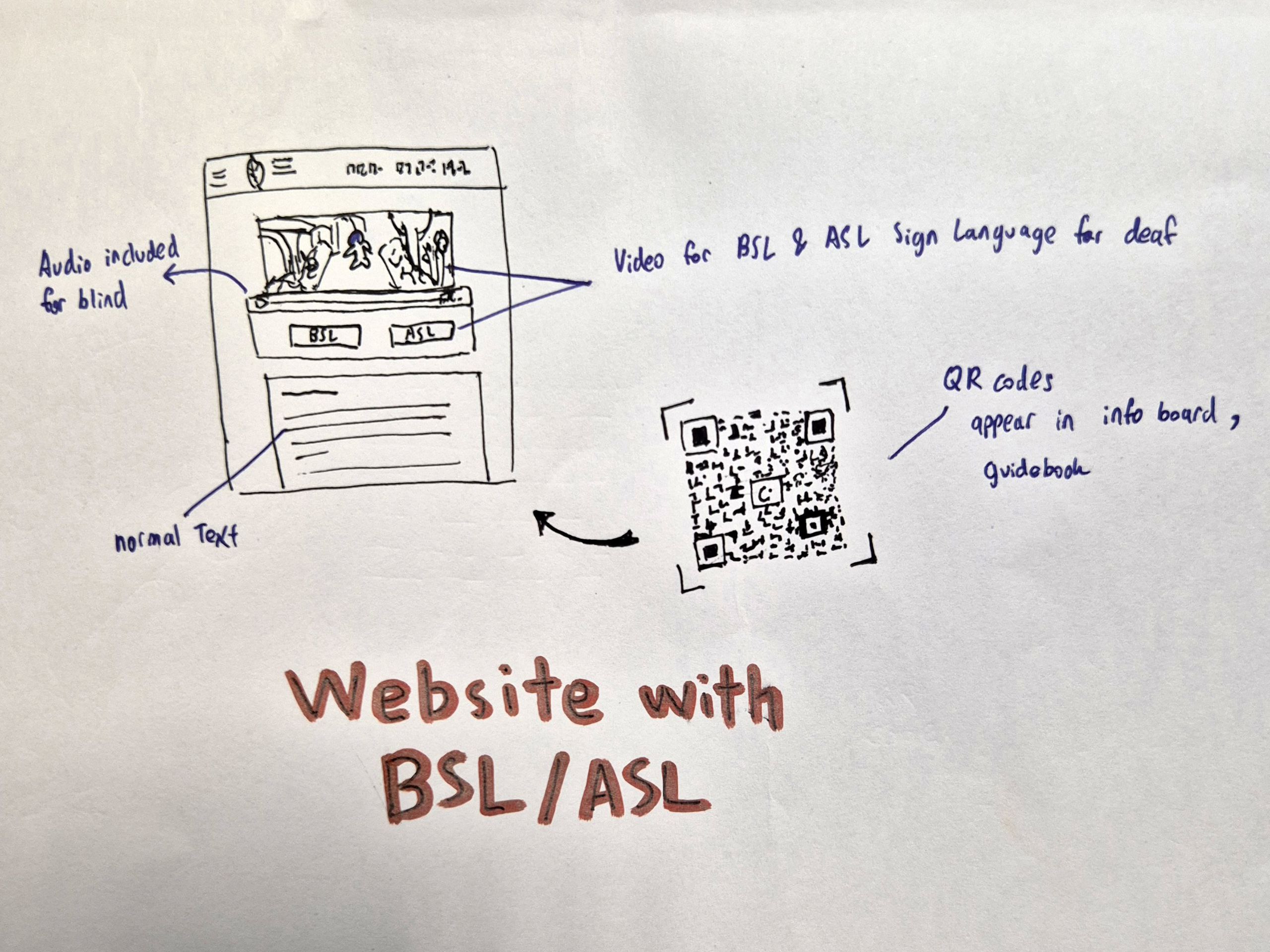

Developing the website became a key focus.

As both a deliverable and demonstration platform, it needed to embody the inclusive principles we advocated.

We ensured compatibility with screen readers, used clear layouts, added BSL video content and audio descriptions, and followed accessibility guidelines throughout.

Balancing functionality and simplicity was difficult, especially when integrating multiple content formats in a coherent way.

The presentation preparation involved crafting a narrative that showed our design process from initial research through to solution implementation.

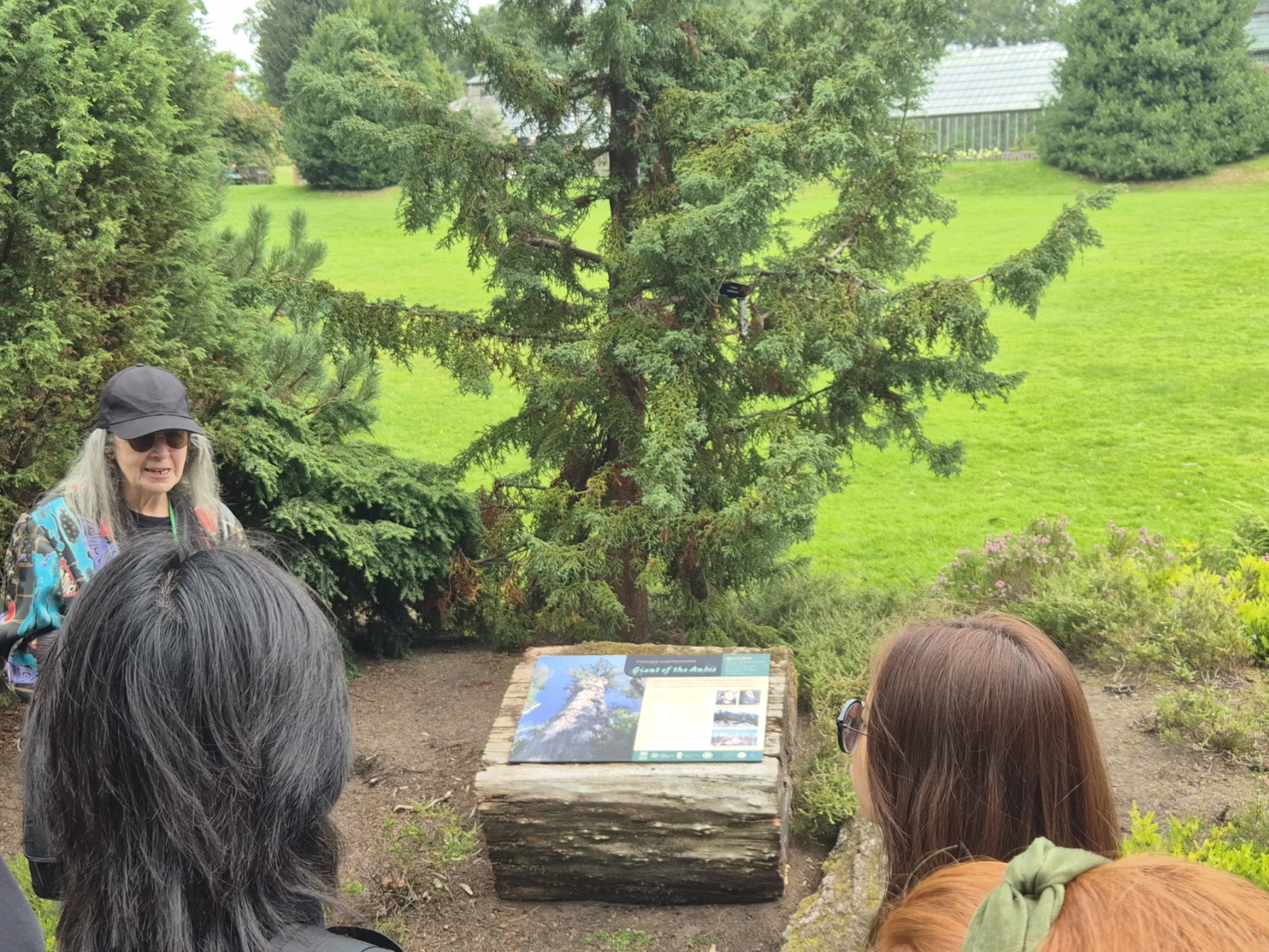

We focused on showing how our ideas addressed the specific accessibility issues observed during fieldwork at the Glasgow Botanic Gardens.

Reflecting on our approach, we recognised that involving users earlier in the process would have allowed for deeper validation of our concepts.

This final stage highlighted the need for inclusive thinking not just in what we design, but also in how we communicate those designs.

Presenting accessibility solutions clearly and persuasively is just as important as making them functional.

The experience also strengthened our ability to link design choices to user needs and project goals.

Overall, this project helped us develop practical skills in inclusive design, usability testing, and communication.

It clarified the importance of testing, iteration, and involving users as early as possible.

These are lessons we will carry forward into future projects in both academic and professional settings.